A decade after Hunter S. Thompson

Too weird to live, too rare to die

They say that one should never meet their heroes. “They can never live up to the ideal person that you’ve mentally made them out to be,” someone once told me. I never got the chance to meet one of my heroes. By the time I first became familiar with his work, he was already dead. In my lifetime, he was an incoherent mess. A crippled shell that had locked away the most rebellious outlaw spirit the literary world was able to abide by.

Perhaps it was better this way. Even now, I don’t think I would be equipped to meet Dr. Hunter S. Thompson. He would probably hate someone like me, anyway. A university student playing at Gonzo journalism. Even still, this being my last year at the Carillon, and a full decade after Thompson’s passing, it seems to me to be too serendipitous to pass up at least writing something of a proper eulogy.

Hunter Stockton Thompson was born in Louisville, Kentucky on July 18, 1937. Thompson’s father died at a young age, leaving the family in poverty. At the age of 17, Hunter Thompson was incarcerated for 60 days for abetting a robbery. After serving only half of that sentence, he joined the United States Air Force. It was working for Eglin Airbase’s newspaper that Hunter Thompson got his first taste of professional journalism. After an honorable discharge in 1958, Thompson began drifting across the U.S. and Puerto Rico, working for every newspaper that would accept an article from him.

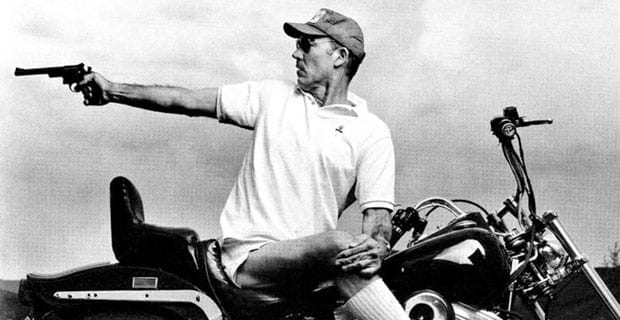

By 1965, Hunter had returned to the United States. He was contacted by then-editor of the Nation, who wanted Thompson to write a story about the California-based Hells Angels motorcycle club. Hunter spent a year living and riding with the gang for research. The resulting article spawned Thompson’s first book, Hell’s Angels: The Strange and Terrible Saga of the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs. After a spat with one of the members, the Hells Angels stomped Thompson, which only led to further publicity for the book, including a CBC Television confrontation between Hunter and Angels member Skip Workman.

The success of Hell’s Angels made it possible for Thompson to start contributing to more prolific newspapers and magazines, but it also gave him a solid relationship with publisher Random House. The royalty check from sales of Hell’s Angels gave Thompson enough money to buy Owl Farm, the fortified compound in Woody Creek, Colorado, where Hunter and his family spent the rest of their lives. A $6,000 advance from Random House saw Hunter covering the infamous 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago. Although that book would never be completed, Hunter’s contract with Random House would be fulfilled in 1972.

In 1970, Thompson ran (unsuccessfully) for the local sheriff’s office in Aspen, Colorado. It was a particularly memorable election, not only because Thompson’s “Freak Power” party posed a viable threat to the Democrat/Republican dichotomy, but because Thompson had set up camp in the offices of Rolling Stone magazine with beer and the promise that he was soon to be the new sheriff of Aspen. Although he was soundly defeated, Thompson had captured the attention of Rolling Stone editor Jann Wenner, who sent Thompson out to do an expose on the murder of television journalist Ruben Salazar. In typical Thompson fashion, he blew off much of that assignment, and instead, took a Sports Illustrated pitch to cover the Mint 400, a race through the deserts of Nevada. SI rejected Thompson’s 2500 word take on their 250-word pitch outright. Thompson then sent the work back to Jann Wenner. This would become part one of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: A Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream.

“We were somewhere around Barstow, on the edge of the desert, when the drugs began to take hold.” I was thirteen when I read the first sentence of “The Vegas Book,” as Hunter would later call it. Like generations before me, I was about to learn a lesson that I was far too young to appreciate. Freedom of speech, the pursuit of happiness, liberty, the fundamentals of North American democracy and of the beloved American Dream—they were all dead. The book was a mainstream success, and it is perhaps, sadly, what Thompson will be best known for.

Within the next year, Thompson wrote extensively for Rolling Stone, covering the 1972 Presidential Election, which pitted incumbent Richard Nixon against Senator George McGovern. Because Nixon did very little campaigning for re-election (and because he and Hunter were bitter enemies by this point), Thompson covered the Democrats almost exclusively. As history played out, McGovern would be handed one of the most disastrous defeats in U.S. political history.

After 1972, however, things began to quickly slide. Thompson’s rampant substance abuse and rebel attitude were quickly catching up with him. After sleeping right through the “Rumble in the Jungle” in 1974, and several cancelled assignments later, Thompson found himself at odds with Rolling Stone, the only magazine with which he would ever find something resembling a steady platform. The 80s and 90s were marred by run-ins with the police and irregular acid-soaked gibberish. Thompson’s ruminations of the 1992 Presidential Election were assembled into Better Than Sex: Confessions of a Political Junkie, a noticeably worse rendition of his campaign coverage from twenty years prior.

In 1998, Thompson’s work enjoyed a minor resurgence in popularity with the release of the film adaptation of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas starring Johnny Depp. Thompson’s “long lost” first novel The Rum Diaries was published soon after the film’s release. 2003 saw the release of Thompson’s penultimate collection, Kingdom of Fear. Many saw it as a vitriolic attack on the turn of the century in America and the attacks of Sept. 11. In mid-2004, publisher Simon & Schuster released Hey Rube: Blood Sport, the Bush Doctrine, and the Downward Spiral of Dumbness, a collection of Thompson’s weekly column for ESPN. On Feb. 20, 2005, Dr. Hunter S. Thompson died from a single self-inflicted gunshot wound. No More Games. No More Bombs. No More Walking. No More Fun.

Of course, this has all just been a very loose recounting of the life and work of Dr. Hunter S. Thompson. After all, the Father of Gonzo produced fourteen books and hundreds of articles. To get into everything would require more space than the Carillon could afford. He’s been the subject of documentaries, cartoons, speaking tours, and other writers’ works.

Thompson had a very unique problem in his life. During a 1978 BBC interview, Thompson admitted that he often felt pressured to live up to the persona that he’d created in Fear and Loathing. Thompson told the BBC that, “I’m never sure which one people expect me to be. Very often, they conflict — most often, as a matter of fact. … I’m leading a normal life and right along side me there is this myth, and it is growing and mushrooming and getting more and more warped. When I get invited to, say, speak at universities, I’m not sure if they are inviting Duke or Thompson. I’m not sure who to be.” Ironic that the very thing that started Thompson’s career simultaneously ended it.

But what does Thompson mean today? It’s been a decade since the death of the outlaw journalist, and some have argued that he’s a relic of the counterculture that he lamented the death of in the 1970s. That’s actually sort of the point of this feature, gentle reader. Thompson often wrote about the malignant ills of society. To him, the status quo was sickly, and he was one of the vocal minorities who could not only see through the façade that was set up by our benevolent leaders, but was going to shout it down. In many ways, the Carillon and Hunter Thompson could be seen as spiritual allies. The tyrants’ foe, the peoples’ friend, illegitimi non carborundum, refuse to accept the plate of bullshit that everyone gives you, fork in hand. Hunter Thompson was more than a reckless and drug-fuelled raver. He was one of the most keen-eyed observers of society, the most dangerous individual the literary world could tolerate, and someone I’m proud to call a hero, even now.

Of course, it’s more than me that matters. I can’t be the only one who was influenced into action by the Doctor. I encourage anyone who wants to, come seek me out, and let me know just how Hunter S. Thompson has affected how you’re living your life. It’s serendipitous that the 10th anniversary of Thompson’s death—Feb. 20, 2015– falls on a Friday, no? I’ll be haunting bars all around the city. Come say “hi,” or come share your Hunter tales with me. I won’t be hard to miss. I’ll be slugging Wild Turkey, with slices of lemon in it, so as to disguise it as iced tea. I’ll be wearing an Acapulco shirt, waving an electric cattle prod around, and I’ll be shrieking about the first time I ever read, “We were somewhere around Barstow, on the edge of the desert, when the drugs began to take hold.”

Buy the ticket, and take the ride. Mahalo.