Microbiologist Brady O’Connor has found bacteria thriving in extreme cold environments

Dear readers and fellow science enthusiasts,

This is our first issue for the winter 2026 semester and what’s better than starting off by diving into the cool world of research in science!

Now, some of you might say I am biased toward topics covering scientific research, and to that allegation I plead guilty. But does that take away from the fact that some super exciting things happen in the realm of science research? I think not. So, let’s dive in!

In this article I present to you the research done by microbiologist and astrobiologist Dr. Brady O’Connor in the polar extremes of our planet. Traveling to the Arctic and the Antarctic, Dr. O’Connor and his team have studied the microorganisms found in these regions.

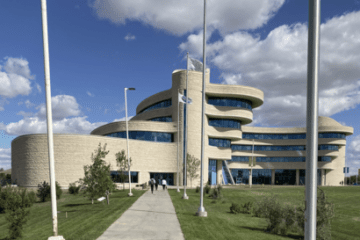

Before we talk more about his work, there is a very important local connection here that must be highlighted. Dr. O’Connor is a University of Regina (U of R) alumnus and was an undergraduate researcher in the U of R’s vice-president of research, Dr. Christopher Yost’s lab before graduating.

Growing up and time at the U of R

The Regina-born Dr. O’Connor describes a typical childhood growing up in the Queen City.

“I was really big into sports […] I did a lot of soccer growing up, went to a lot of Saskatchewan Roughriders games, [and] liked playing hockey,” he said during his conversation with the Carillon.

Ironically, he was not very interested in the sciences as a kid. He says his passion for the subject only began during his senior high school years.

“Originally, I thought about becoming an engineer. And then at a certain point, I realized that I wasn’t as interested in applying science […] I was more interested in actually making discoveries.”

He enrolled into the U of R with dreams of becoming a marine biologist and hoped to move to British Columbia to study marine animals like whales and dolphins. Becoming a microbiologist was not in the plans until he took a required microbiology course with Dr. Yost. “He just kind of really fascinated me into the field of microbiology […] I kind of changed my whole career path after that,” he said.

Dr. O’Connor joined Dr. Yost’s lab, the Institute of Microbial Systems and Society (IMSS), which became his break into the realm of research in microbiology. “Chris and IMSS gave me an opportunity to join a real research lab […] I kind of owe everything in my career to that start with IMSS. If it wasn’t for that experience, I wouldn’t have been able to get my position at McGill for my PhD,” he shared.

In an email response to the Carillon, Dr. Yost recalled Dr. O’Connor’s time in his lab as an undergraduate researcher. “I would say that one of Brady’s most distinguishing characteristics was his initiative and enthusiasm.” He shared that he expected Dr. O’Connor to go on to have great accomplishments in microbiology. “Once [Brady] recognized that he was interested in microbiology he was very focused and sought opportunities to expand his experiences in microbiology, and this provided him with the opportunity to go to McGill and a high impact research group for his grad studies. It all comes back to enthusiasm and initiative,” he said.

Dr. Yost concluded his response by saying that he is very proud of Dr. O’Connor’s accomplishments and glad that the U of R was able to introduce him to the world of microbiology and support his professional development.

I had always thought space and space travel was really cool as a kid. So I thought, oh, here is a way that I could combine those two passions, microbiology and space research.” – Dr. Brady O’Connor

Current work and findings

After finishing his undergraduate degree at the U of R, Dr. O’Connor did his PhD at the McGill University before starting his current postdoctoral position at Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center at Ohio State University in the United States.

He says a big part of his research takes place in the Canadian High Arctic with the primary sites being the Axel Heiberg Island in the Canadian Nunavut territory just below the 80°N latitude and the Devon Island ice cap which is the largest uninhabited island in the world. In addition, he has worked at Livingston Island near the Antarctic Peninsula and with sediments in the Southern Ocean, beneath the Ross Ice Shelf, just off the coast of Antarctica.

He explained that the main goal of his research is to understand whether these extreme environments contain living, breathing, and metabolically active microorganisms. “We’re really trying to determine to what extent there are active microbial communities in these environments, given how extreme that they are. One of the projects we have is trying to use some of these microorganisms, especially the ones that are trapped in glaciers and ice sheets, as climate proxies.” He elaborated that by studying these microbes they can learn about the Earth’s past climate. “Similar to how ice core scientists will use, let’s say, the atmosphere trapped in ice cores to determine something about the way the Earth’s climate used to be,” he explained.

He shared that his team found photosynthesizing and organic carbon producing bacteria one to two metres below the surface of ice in these biomes which, until recently, were considered to be lifeless.

“We think that they’re surviving in these really microscopic liquid veins of water.” He explained that as the water freezes into ice within the glacier, it expels any kind of impurities, salts, acids, or dust grains that are in it and those don’t get frozen into the ice. “[This] makes these really concentrated veins of either acidic or salty water […] We think that that’s where [the bacteria] are living.”

He further elaborated that the results of his research shows the presence of a large population of cyanobacteria that can photosynthesize and are considered as primary producers in these extreme environments. This shows the presence of an entire little ecosystem there.

“That has implications in a few different ways […] it suggests that there could be microorganisms that could have evolved and survived in similar environments in other places within our solar system. One of those being Mars [since] Mars has a lot of ice on it […] or even on the icy moons of Jupiter and Saturn, which have basically these large ice crests that actually hide a liquid water ocean beneath them.”

Working in this field allows Dr. O’Connor to combine his love for space and microbiology. “I had always thought space and space travel was really cool as a kid. So I thought, oh, here is a way that I could combine those two passions, microbiology and space research,” he exclaimed.

Future research

Dr. O’Connor says his team is beginning to look into the effects of climate change on these microbiomes as they continue their studies. “We really need to understand how these changing environments are impacting these microorganisms and then how they in turn affect future climate change,” he concluded.

My conversation with Dr. O’Connor only deepened my interest in science and more specifically microbiology. In the end, I stand by what I have always said, science and research in science are super cool!