U of R book series

An analysis of philosophical heavy hitter John Locke

Article: Michael Chmielewski – Editor-in-Chief

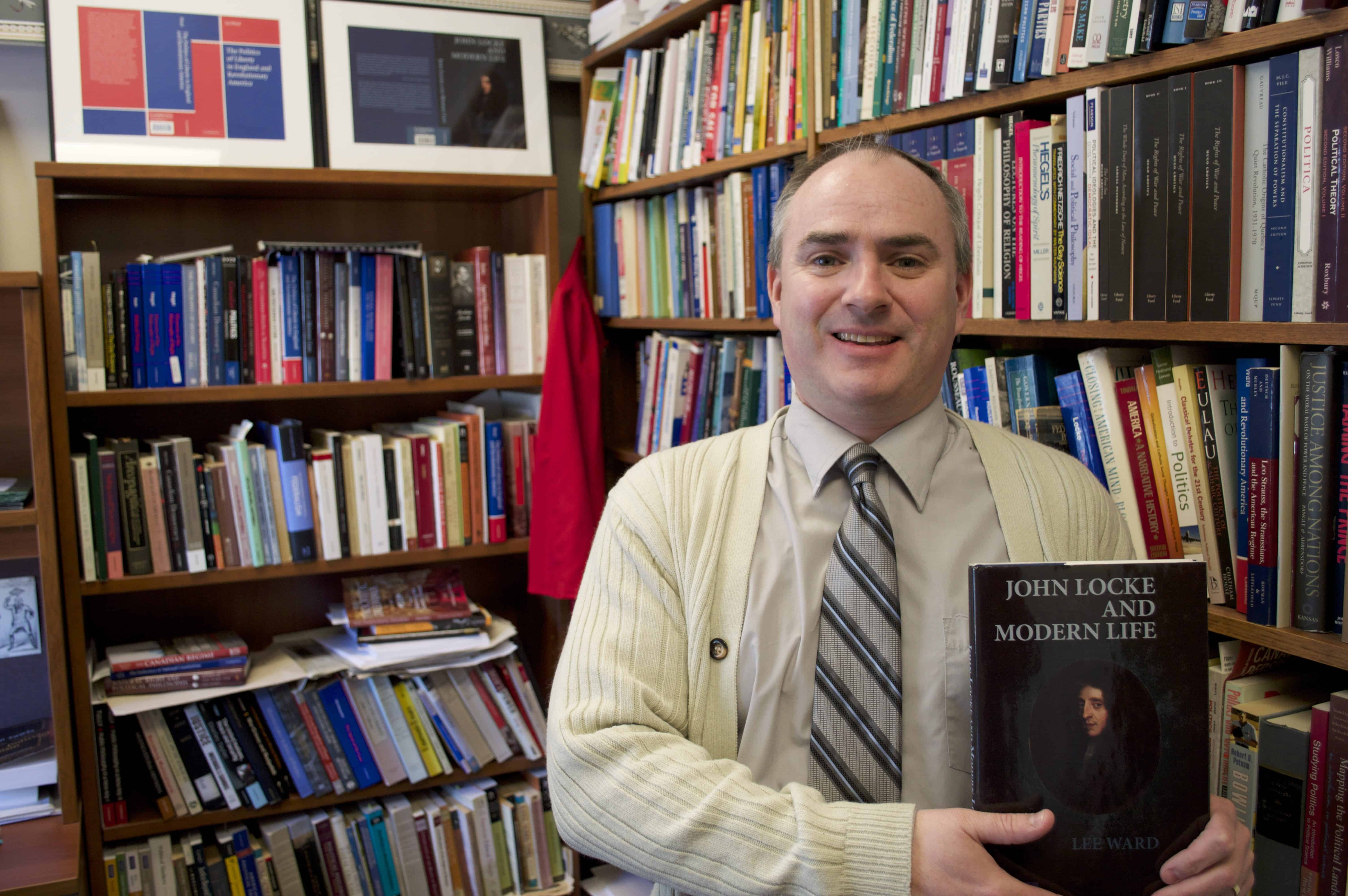

[dropcaps round=”no”]“I[/dropcaps]n the history of philosophy I’d definitely put him in the top tier, because the top tier of political philosophers are the ones who have created a legacy. For generations or centuries after them everyone sort of responds to them, so I’d put Locke in the same category as Aristotle, Plato, Thomas Aquinas, the great thinkers that dominated their era and well after,” says Lee Ward, Campion College associate professor of political science at the U of R.

John Locke, the 17th century English philosopher, is the subject of Lee Ward’s book, John Locke and Modern Life. The book “recovers a sense of John Locke’s central role in the making of the modern world,” rejecting the idea of Locke as an “intellectual anachronism,” states the preamble.

Locke, the author of Two Treatises of Government, was an “interesting guy all around,” says Ward. In his book, Ward writes about Locke’s contribution to the modern world in seven different chapters: “The Democratization of the Mind, The State of Nature, Constitutional Government, The Natural Rights Family, Locke’s Liberal Education, The Church, and International Relations.”

Writing a full chapter of this last topic, international relations, came as a surprise to Ward.

“One of the things that surprised me was how much interesting discussion, and how rich, Locke’s account of international relations is.”

“I had always assumed that the classical liberal idea of international organizations, so the precursors to the idea behind the UN, was more of an 19th century creation, definitely a very Victorian idea, which I supposed started with [Immanuel] Kant, so the very beginning of the 19th century, and then developing as the English Victorian idea until you get to Woodrow Wilson and the American ideas of the 20th century.”

This is a novel discovery because Locke does not get enough credit for his ideas on international relations like his philosophic successors.

Since, as mentioned before, Locke is not a historical anachronism, it would be an interesting thought experiment to ponder what Locke would think of the last 300 years of history, and the modern world.

“I think in many respects he’d be thrilled and delighted and pleased to see the spread of democracy, [and] the spread of constitutional governments. Think when Locke was writing, how many nations/peoples in the world had constitutional governments? Only a handful,” Ward says.

“And the idea of constitutional governments that are dedicated to the protection of individual rights and to the notion of human dignity, I think Locke in many respects would say it’s gone very well.”

Yet, in other respects, Locke may not have such favourable praises to sing. One of these areas would be religious fundamentalism.

“In some respects we see greater religious toleration in the world today than we had in the past, particularly in the West, Europe and North America, and yet in other places we’ve seen in the past 20 to 30 years an increase of religious extremism and violence,” points out Ward.

John Locke and Modern Life is another incredible U of R book. Ward’s study of this interesting and important philosopher who’s work had great influence on our age makes it a must read.

[button style=”e.g. solid, border” size=”e.g. small, medium, big” link=”” target=””]Image: Michael Chmielewski[/button]