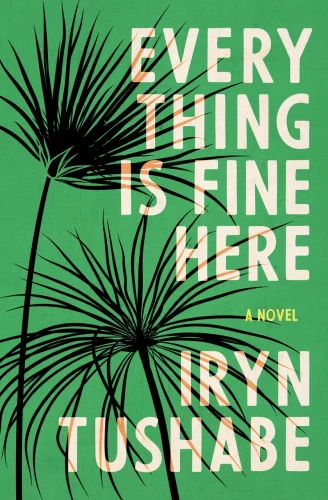

Everything is Fine Here rooted in Ugandan-Canadian’s life experiences

2025 will be a year to remember for Iryn Tushabe, whose first novel Everything is Fine Here was released on April 22.

In her work, the Regina resident digs into her life history to tackle such complicated issues as sexual identity and immigration.

The Carillon’s Eric Stachowich interviewed Tushabe and discussed her book and experiences growing up in Uganda.

What is Everything is Fine Here about? (no spoilers)

Tushabe’s publishing company House of Anansi describes the novel as “A beguiling coming of age novel set in Uganda in which a young woman grapples with the truth about her sister in a country that punishes gay people.”

The novel’s protagonist is Aine Kamara, an 18-year-old girl whose older sister Mbabazi introduces her to her girlfriend. They are in a country with strict and repressive laws targeting LGBTQ+ people.

The novel’s characters are forced to make life altering decisions, sometimes regarding their own mother, who holds strong religious beliefs about homosexuality and is not accepting of her sister’s new partner. The story unfolds as they try to break out old traditions and beliefs and embrace her sister’s identity.

Overarching themes

“Aina’s sister, the older sister who is the gay character, is very closed off. She doesn’t share too much,” Tushabe said. “When Aina is very curious about queerness, and asking questions of her sister, she’s not very forthcoming with answers. But Mbabazi’s partner, Achen, is the one that Aina kind of gravitates toward.”

In the book, the protagonist is able to form a community with Achen where they surround themselves around others who identify as queer or who accept them for who they are.

“That’s kind of what I always want to point to emphasize, is that the strength is in the communities we form around ourselves, is in the ways that we find to navigate a world that would rather we didn’t exist, that sort of thing,” said Tushabe.

I was always thinking about queerness, because I grew up a bisexual woman in a country that has anti-homosexuality legislation. – Iryn Tushabe

Author’s inspirations for writing a novel, rather than non-fiction

“I was always thinking about queerness, because I grew up a bisexual woman in a country that has anti-homosexuality legislation,” said Tushabe.

Tushabe chose to do the novel as a fiction novel, rather than an autobiography or memoir, for a few reasons. One of which is how the truth is often focused on violent aspects in Uganda.

“Instead of focusing on the violence perpetrated by state actors, I wanted to turn the lens onto the queer characters themselves, and how they survive that kind of violence, and how they build communities around themselves, kind of just the beauty of queer existence,” Tushabe said.

She wanted to have a unique way to explore the theme of sexual identity. Tushabe said she had seen this discussed a lot in other LGBTQ+ people’s actual accounts of their lives, but perhaps less so in fiction.

“I realized that if I could fictionalize it, and actually come at the story, from the perspective of someone who actually isn’t queer,” said Tushabe.

Tushabe added that, “In the novel, the older sister and her partner are able to help the younger sister who is straight and privileged, emerge into adulthood, with the kind of compassion and world knowledge she would never get from their mother from the family. So I saw different opportunities to broaden the perspective in fiction than I ever could do in non-fiction.”

Battling her own identity

Tushabe recalled growing up Christian and trying to convince herself that she was not bisexual.

“There is the psychological torture of knowing who you are, but living in a world that tells you that that’s not a way to be, and you need to change that,” she said.

She continued to battle with her identity after arriving in Canada. She said she often prayed to God to rid herself of her bisexuality. But shortly after things started to change.

“When I came to Canada, I think I was already in the process of questioning my Christianity, but it was kind of one day I was convinced that there was no God, another day I was just always finding community in the church,” said Tushabe.

She credits the countless hours spent in the Archer Library as something that helped her find her true identity.

“I feel like I traded Christianity for fanaticism about reading, because I found answers in books that nobody could ever, like, I could never ask a question about, ‘how do I move through the world as a queer black woman?’”she said.

In the process of reading countless books, she became disillusioned with her own Christianity and accepting of her sexuality.

Tushabe’s home country has oppressive rights for LGBTQ+ people

Today Tushabe continues to identify as bisexual and her home country of Uganda continues to be one of the most oppressive countries in terms of same sex relations and rights. In 2024, the Uganda Constitutional Court upheld all provisions from the Anti-Homosexuality Act passed in 2023.

The act contained provisions to restrict availability of healthcare to LGBTQ+ people, and forbade the renting of homes to them. The court did eliminate these provisions, but it kept many others.

In Uganda, freedom of speech regarding LGBTQ+ topics is limited. You can be sentenced to life in prison for having intercourse with a person of the same sex and “promoting” such activity can mean 20 years in prison and heavy fines.

In the most extreme cases, individuals are subject to the death penalty. The Ugandan government describes these people as being guilty of what they term “aggravated homosexuality.” That includes such offences as same sex intercourse with a person younger than 18 or older than 75, repeat offences, sex with a mentally ill person or person with a disability and sex with anyone with a prior offence.

There are other reasons such laws exist, one reason is colonialism. “Uganda was colonized by the British, and they were the first to introduce this law as part of the penal code,” said Tushabe.

This legislation was not enforced until 2009 and it was something that Tushabe, while growing up, didn’t even know existed.

“It got reintroduced after a massive seminar that was put on by American evangelists visiting the country as part of their proselytizing and spreading this homophobia under the pretense of … maintaining traditional families,“ she said.

Corruption is another reason these laws still exist, Ugandan president Yoweri Museveni has been in power since 1986 and “behind the scenes a lot of the politics is dirty and is violent and is massively corrupt,” Tushabe said.

“If they focused as much energy on developing the country as they do on nonsense laws like this, the country would be so much richer and better, and it’s just sad that many Ugandans can’t see that, “ she added.

I feel like I traded Christianity for fanaticism about reading, because I found answers in books. – Iryn Tushabe

Deep roots with the university

Tushabe came from Uganda in 2007. She completed two degrees at the U of R: film in 2012 and journalism in 2013 .

She says this has always been a place where she felt accepted and able to explore her true identity.

Author’s future plans

“I’m infinitely inspired by nature. I grew up near a forest, and the village of my birth no longer exists has been kind of consumed by the forest because we actually lived in a migratory corridor for animals, for elephants,” she said.

She is fascinated in writing about things that are beyond the human sphere and how all life is interconnected.

Tushabe is eager to get started on her next book, where she can tackle things she is passionate about – and delight her fans.