U of R book series

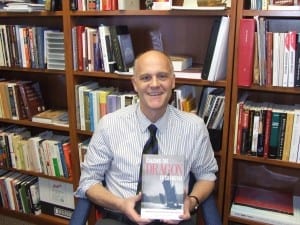

Zone of Encounter: John Meehan and Chasing the Dragon in Shanghai

Article: Liam Fitz-Gerald – Contributor

[dropcaps round=”no”]I[/dropcaps]n recent years, contemporary media has been fixated on the rise of China as a political and economic force. Some of that concentration has focused on the reaction of western countries. Dr. John Meehan, President of Campion College and a professor of history at the University of Regina, has catalogued Canada’s early relationship with China in his 2011 book Chasing the Dragon in Shanghai.

Meehan is no stranger to East Asian history and Canada’s connection to it. His doctoral thesis, which later became the basis of his book The Dominion and the Rising Sun, examined Canadian relations with Japan from 1929 to 1941. It was the research behind this thesis-turned-book that got Meehan interested in China, specifically Shanghai.

“While researching for my PhD thesis, I realized that the other area of Canadian activity at that time was China, and specifically Shanghai,” Meehan said, admitting that he was fascinated by the different layers of Shanghai.

“It was really a cosmopolitan city, where people from many different cultures would meet and mix and mingle.” He continued saying the city was a “zone of encounter” between east and west.

“There were over 200 Canadians at any given time in the 1940s, so I became intrigued of who these people were and what kind of influence they had.”

Meehan examined the period 1858-1952, from Lord Elgin’s arrival in Shanghai to when the final Canadian “Shanghailanders” (European residents of Shanghai) left the Communist ruled city. Even though Canada and the People’s Republic of China celebrated forty years of Ottawa’s recognition of the Communist state in 2010, Canada’s relations with China existed prior to 1970. Yet Canadian historians initially overlooked relations with East Asia, focusing on relations with the United States and Europe. In recent years this has changed; partly from China’s ascension as an economic power as well as Asian Canadians playing a more pivotal role in business and politics.

Meehan focuses on the role of Canadian missionaries, business people and everyday Shanghailanders. While missionaries had religious motives, many took up social causes such as promoting women’s education and ending the practice of foot-binding. Canadian business delegations came over to for trade, initially focused on agricultural ventures.

Yet many Chinese were unhappy with the Canadian presence. From 1923 to 1947, Canada excluded Chinese immigrants and many Shanghai Chinese protested Canadian trade delegations as a result. Furthermore, many Chinese resented the European Shanghailanders, who were not subject to Chinese law, but the law of their respective country. Canadians were also afforded this privilege of extraterritoriality.

“Many Chinese found that the Shanghailanders in these foreign enclaves weren’t subject to Chinese law and enjoyed a prosperity that many Chinese did not have, so [extraterritoriality] was seen as an insult to the Chinese people,” he explained, saying that when extraterritoriality was abolished in 1943, it was seen as a triumph of Chinese nationalism.

Shortly after the WW2, the Communists established control over the mainland. In 1949, Canada was prepared to recognize the Peoples Republic of China, but this did not happen until 1970.

“The United States was a huge factor in why this did not happen. McCarthyism was about to take off and Communist China was seen on the same page as the Soviet Union. Another factor was Quebec. The Catholic Church was staunchly anti-communist and so Ottawa backed off,” Meehan said, explaining why it took twenty-one years for Canada to recognize China.

Meehan highlights that the period was a formative one as it foreshadowed the types of Canadians who went over to China later, such as academics and business leaders. Yet he also highlights how mythmaking impacted relations with China.

“This wasn’t a region that many people knew about so many Canadians went over there with unrealistic expectations of China being an unlimited market that would solve all of Canada’s economic woes. It wasn’t and I think it’s a caution to people today to say yes there is potential in China today but let’s be realistic,” he said, emphasizing that many Canadians were ignorant about the country they lived and traded in.

“There are many challenges to dealing with China, cultural and political sensitivities. These are all things Canadians have to take into account.”

[button style=”e.g. solid, border” size=”e.g. small, medium, big” link=”” target=””]Image:Liam Fitz-Gerald, Michael Apel[/button]