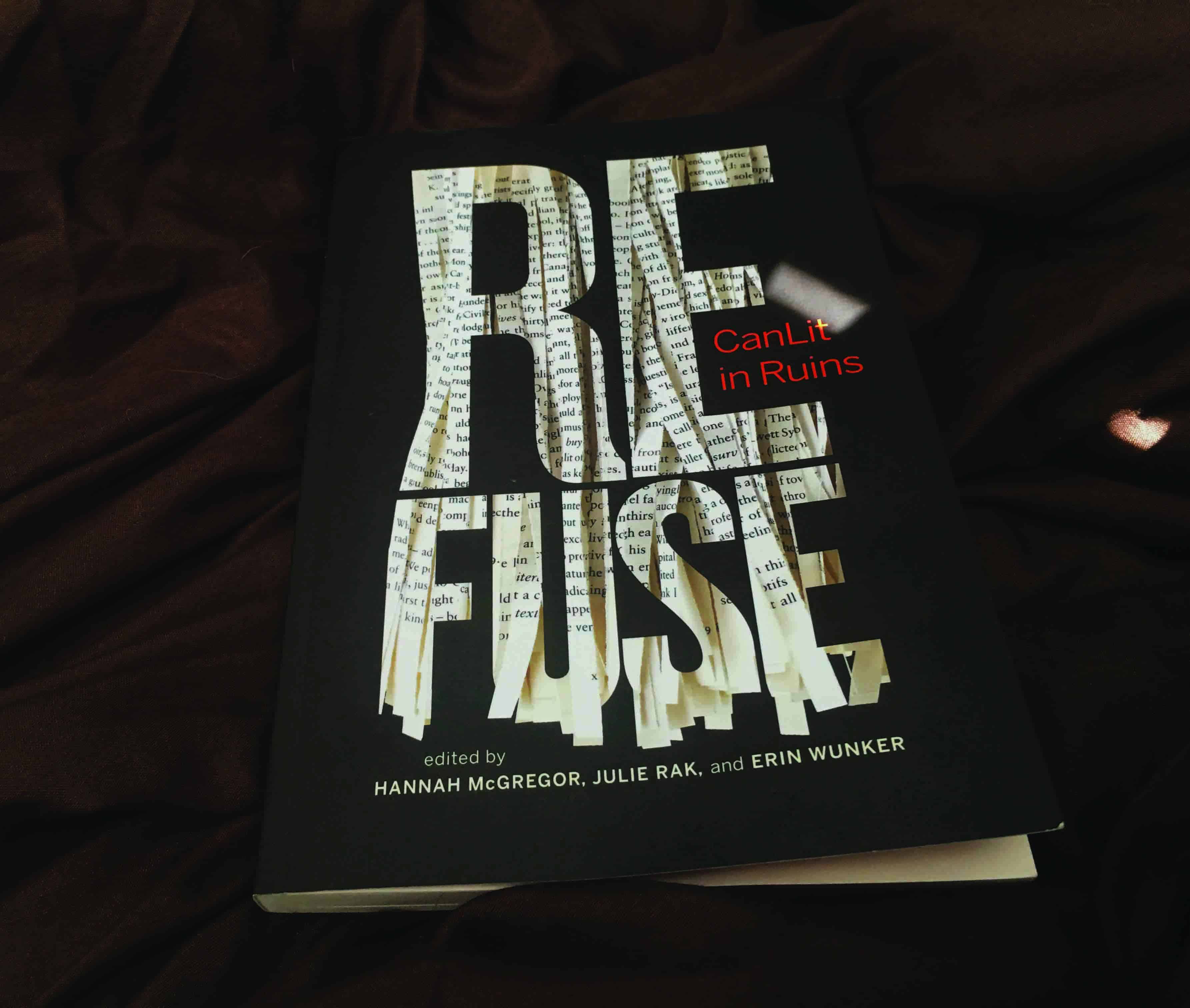

Can Lit in Ruins

author: john loeppky | editor-in-chief

And so it lay smoldering / John Loeppky

Book challenges a contentious climate

The operative word for this gutsy volume, tackling the current Canadian literary scene with all its lawsuits, accountability letters (courtesy of UBC), and poisonous underbelly, is defiance. The title of Alicia Elliot’s essay encapsulates the tone of the book well, “CanLit Is a Raging Dumpster Fire.” The title being more apt to me, as a reader, than the suitably well constructed introduction as it stands more nuanced in its combativeness.

Refuse: CanLit in Ruins is a word-wielding rebuttal to the current literary climate in Canada. The introduction offers one meaning of the word “refuse” in their words, “‘Refuse’ is another word for garbage, for waste. And what wastes our time, and our lives as writers as teachers, is the kind of endorsement of the status quo that we want to see taken out of CanLit.”

What makes this book worthy of significant praise, however, is its tendency to focus on the second meaning that they provide for the title, that of a coming together or, “….to put together what has been torn apart.”

Refuse refuses to track along just one literary mode and brings together a multitude of significant voices who, it is obvious, feel marginalized in their opinion on the subject. From Gwen Beneway’s striking poem “But I Still Like,“ which delivers a gut punch early with “our legendary writers/moonlight as rape apologists.” There is no hiding from the intent of this anthology.

For those unaware, Lucia Lorenzi’s essay, “#CanLit at the Crossroads: Violence is Nothing New; How We Deal with it Might Be,” provides readers with the necessary background to contextualize the fearlessness of, not only the writers, but those they defend – as is named, on the first page “for all the complainants.” A number of the writers involved take aim at Margaret Atwood; unsurprising, given the widespread backlash faced by the Canadian legend after her partial penning of the UBC Accountable letter admonishing UBC for their handling of the suspension of Professor Steven Galloway.

For me, the strength of this work lies in the mixture of poetry and essay that defines its construction. The aforementioned Beneway poem aside, Kai Cheng Thom’s “refuse: a trans girl writer’s story” questions the word community and how it relates to the literary world around her, “can you refuse something/that was never offered to you?” Thom’s ability to use the repeated metaphor of garbage present throughout the collection, “and my writing grew/ like dandelions in a trash heap” as well as reclaiming the violence so obviously used against her in her career, “i mean, seriously/ crack open ‘CanLit’/ how many skinny chinese fags/ can you find?” reads as much a calling out as a calling in of those who have not been considered before. Thom’s accosting of an unwelcoming literary scene is echoed in Chelsea Vowel’s “No Appeal” where she voices those viewed as hypocrites for what I would call a selective accountability approach. In Vowel’s words, “we believe women we believe you but not you he’s our buddy witch hunt/ twitter mob/ hope you weren’t planning on making a home here our literature is about/ you not for you.” To which I say, preach, more please.

It’s important to note that this defiance of an establishment unwilling to include voices silenced is not confined to the poetry of the book. A. H. Reaume’s “In the ‘New CanLit,’ We Must All be Antigones” where she references the famous Greek character as an example of modern day activism in order to remind the reader of their position in this landscape with a pointed question.

“How have marginalized writers been silenced in CanLit?”

“To start with, marginalized people have been told explicitly or in so many words by publishers and lit magazines that their stories aren’t ‘universal’ enough.”

Review-wise it is refreshing to read a book that has absolutely no interest in being conciliatory and is adversarial in a (hopefully) fruitful way. Refuse mentions the battleground that is Twitter without devolving to slinging the same old short-form refrains. Instead this book provides needed context, sparing no one worthy of critique (in their eyes), and embraces the need to tackle the topic at hand with a variety of voices. If the pen truly is mightier than the sword, then the editors of Refuse have created finely tuned instrument of literary battle – even if they would, I’m sure, critique the use of a violent metaphor to champion their work. Let me rephrase, Refuse disavows any notion that our literary scene is in no need of critique while presenting tangible options in moving forward and breaking new, more inclusive, more caring, ground. Refuse: CanLit in Ruins is readily available from Book*hug Press