The Forgotten Huxley: Drugs That Shaped His Mind

bodie robinson | a&c writer

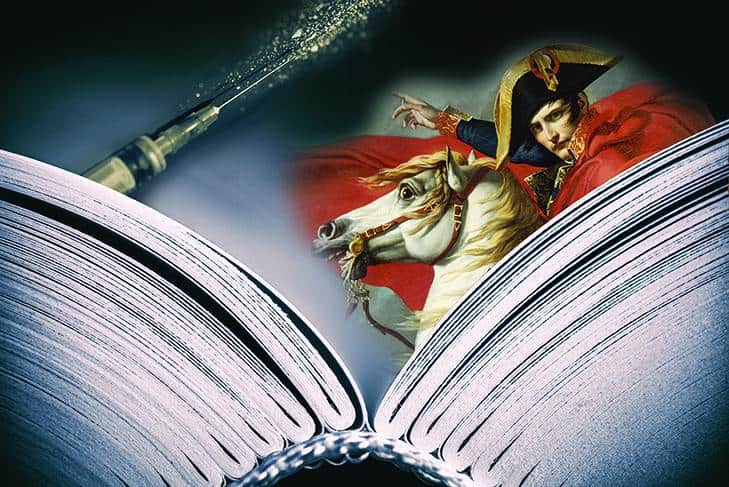

Photo credit: Christian C, Jean Pierre, Dalbera, and Oli Henze on Flickr.

We’re getting bookish with Bodie again, guys!

The name Aldous Huxley and visions of a futuristic totalitarian dystopia are synonymous. If you ask anyone about Aldous Huxley, the first thought that comes to mind is his 1932 novel Brave New World. This novel is Huxley’s magnum opus: the futurist complement to Orwell’s 1984. Unfortunately, writers and artists can’t decide what posterity will remember them for. And the same problem befell Mr. Huxley. We remember him for the wrong reasons.

Huxley’s fiction is not good. The prose is droning and unimaginative. Chapters, especially in his 1962 novel Island, seem to drag along crudely and bump into one another without subtlety or ingenuity. There is no doubt that Huxley’s genius is present in his novels, but his presentation is unimpressive. His ideas on politics, religion, and society linger on the page, but they are never adequately articulated. The novel simply wasn’t his domain.

Huxley was an Oxford man. During his time there, he studied English. He graduated with a Bachelor of Arts with first-class honours. It was here that he learned, and began to refine, his true art – the essay. It’s in his large collection of essays where we find the forgotten Huxley. Huxley feels free to express himself and his ideas through his own voice: his potent critical thinking, British charm, sensitivity, modesty, and his acute attention to every possible aspect of an essay.

The essays on mysticism and psychedelic drugs are where Huxley reaches his zenith in creativity and expression. Huxley’s interest in mysticism and esoteric religion go back to his 1945 book entitled The Perennial Philosophy. This 300-page study enumerates many of the fundamental concepts within mystical thought, by examining thousands of quotations from the scribblings of sages and mystics throughout history. The Perennial Philosophy adumbrated Huxley’s later obsession with psychedelics and drug-induced religious experiences.

Drugs that Shape Men’s Minds was an essay that Huxley released in 1958. Having taken mescaline (the psychedelic compound in peyote mushrooms) a few years prior, and then moving on to occasional LSD use, Huxley began meditating on the role that drugs played in human history. He was interested in how drugs and other altered states of consciousness have influenced religion and theology.

The question: why is humanity so obsessed with altered states of consciousness? Why should humans want to take drugs so readily in order to escape their everyday consciousness? “There is a paradox here, and a mystery,” Huxley writes. “Why should such multitudes of men and women be so ready to sacrifice themselves for a cause [i.e., drug addiction] so utterly hopeless and in ways so painful and so profoundly humiliating?”

The answer: because humans have, for many millennia, used drugs in order to transcend themselves and experience a set of feelings and thoughts that can only be described as “religious” or “spiritual.” Huxley says it better than I ever could: “The problem of drug addiction and excessive drinking is not merely a matter of chemistry and psychopathology, of relief from pain and conformity with a bad society. It is also a problem in metaphysics—a problem, one might say, in theology.”

If, as it seems, humans do have a congenital impulse to get intoxicated, to transcend their normal consciousness, then what is the best way to do this? Huxley’s prescription is the psychedelic drug. The psychedelic is extremely potent, so there will be no question about whether a transcendent experience will occur. And, in contrast to alcohol and other hard drugs, psychedelics have little to no averse side effects. Here Huxley, writing in 1958, predicted the psychedelic craze of the 1960s hippie movement.

“Physiologically costless, or nearly costless, stimulators of the mystical faculties are now making their appearance, and many kinds of them will soon be on the market. We can be quite sure that, as and when they become available, they will be extensively used. The urge to self-transcendence is so strong and so general that it cannot be otherwise.”

Although Huxley warns against excessive exaltation of the psychedelic experience, he nevertheless offers it as a solution to one of the biggest problems our culture has struggled with since The Enlightenment. That is, what is to be done about religion? Clearly, organized religion has lost its grip on our society and it continues to fade as technology and science advance. But what about the human need for self-transcendence; for “god intoxication;” for spiritual fulfillment?

Well, psychedelics offer a sensible approach. In the psychedelic experience, there is no religious dogma, no scripture, no perfunctory tradition. There is only “direct experience of self-transcendence into the mind’s Other World of vision and union with the nature of things.” Therefore, Huxley concludes, “a religion of mere symbols is not likely to be very satisfying. The perusal of a page from even the most beautifully written cookbook is no substitute for the eating of dinner. We are exhorted to ‘taste and see that the Lord is good.’”