Researchers are digging up Saskatchewan’s prehistoric past be it dinosaur diets or ancient microfossils

University of Regina’s earth science department has made some cool strides in the terms of research. Ben Egan, a master’s student is currently working on a project known as the carbon isotope anomaly, which involves dinosaurs eating patterns. Professor Maria Velez has also been an active researcher of microfossils at the U of R and conducted many experiments, which give a glimpse of what Saskatchewan looked like millions of years ago.

U of R student researcher conducting fascinating experiment

Ben Egan has been working on a project called the carbon isotope anomaly, which is a discrepancy between what was thought about dinosaurs’ diet and what the existing fossils of their bones and teeth are telling the researchers.

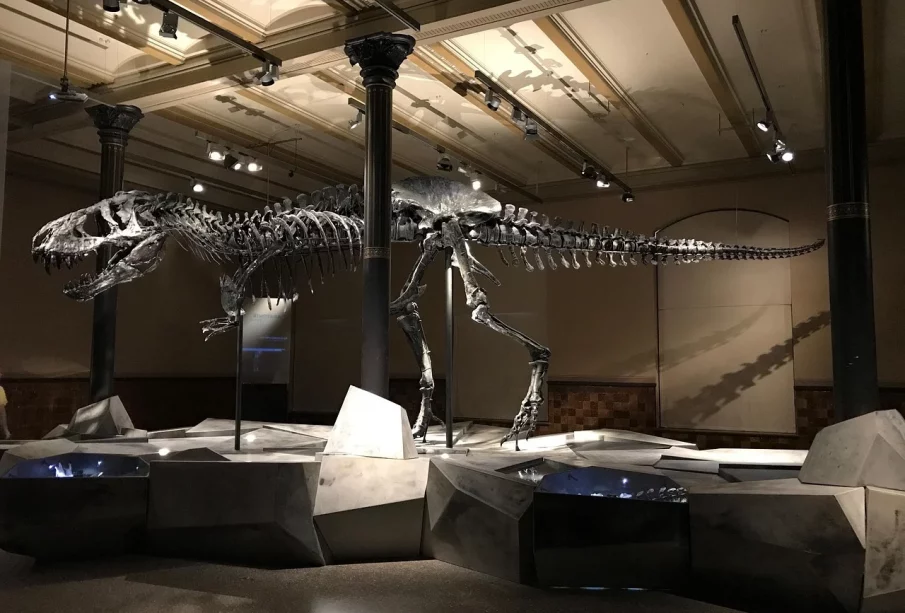

He has been fascinated by the world of dinosaurs from a young age, citing films such as Jurassic Park (1993) and Walking with Dinosaurs (1999 and 2003) as inspirations.

“When we take that modern understanding and apply it to dinosaurs, it doesn’t really make much sense. These animals have very weird carbon isotopes, and it’s basically become the carbon isotope anomaly,” said Egan

The anomaly is the primary subject of Egan’s master’s thesis and believes that he may have figured out a way to study this anomaly.

Problem solved?

Egan believes the solution lies in comparing the carbon isotopes in dinosaur teeth to the isotopes that are found in amber or fossil tree resin.

“Its amber can tell us a lot about what the plant tissues looked like. It’s able to lock in its carbon isotope value for millions of years unchanged. And that’s something kind of rare in the fossil record,” Egan said.

Egan said that by comparing the presumed diets of dinosaurs and their teeth can hopefully give a better understanding of why the anomaly exists.

After two years of research, Egan hopes to publish his findings sometime in the coming October or November.

Career going forward

Egan enjoyed the opportunity of working with undergraduate students at the university during the summer. “It felt like we were doing some really good science,” said Egan.

He also mentioned enjoying the opportunity to do research in Saskatchewan. “Paleontology is quite understudied in Saskatchewan when you compare it to Alberta. But the rocks here do have the chance to show just as amazing stuff,” said Egan.

He added that “It’s a lot rarer to find fossils, but there’s a good chance we’ll find some really cool things in the next couple of years that will change our understanding of dinosaurs entirely, hopefully.”

Egan hopes to do future research on the chemical makeup of dinosaurs.

Saskatchewan is one of the few places where we can see all these environments before the extinction and after the extinction. – Maria Velez, micro paleontologist

What exactly is paleontology?

Paleontology is described as being the study of life that existed a long time in the past. The mechanism that paleontologists use to study the past is fossils. Fossils can be best described as any preserved remains of an organism that existed in the past. Fossils are one of the ways we can understand how the earth and ecosystems have evolved over time.

Recently, the U of R has been conducting research in the field of micro-paleontology which is a branch of paleontology that focuses on studying microfossils. Maria Velez is a micro-paleontologist at the University.

“Some people may think that vertebrates and dinosaurs are cooler than little, tiny, microscopic organisms. But at the end we’re doing the same, we’re using the fossils to get to know something that we don’t see anymore, is long gone, is extinct,” said Velez. She added that it is harder to extract bones for animals and other large fossils, but for microfossils it is much easier.

Saskatchewan’s landscape serves as a time machine

Velez has worked on researching how tiny, microscopic algae known as diatoms first appeared on the earth. Saskatchewan is in a unique place when it comes to the diatoms.

“Saskatchewan has one of the oldest rock units that contains evidence of that evolution. It’s pretty exciting. I have been involved with looking at the record of freshwater diatoms in Saskatchewan,” said Velez.

Velez collaborated with the Royal Saskatchewan Museum, where she supervised students who studied the extinction of the dinosaurs, at the end of the Cretaceous period, which existed around 145 to 66 million years ago. The extinction was caused by a massive meteorite.

“Saskatchewan is one of the few places where we can see all these environments before the extinction and after the extinction. So, we are uniquely positioned to see that,” said Velez.

She further added that, “[Saskatchewan and Alberta] are a fabulous archive of rocks that contain the history of the Earth in one of the key periods of evolution,” as she explained how millions of years ago Saskatchewan and Alberta used to be under an ocean.

Velez explained that during this time there was a depression or a sunken landform, which allowed sediments and rocks to pile up. This process continued, long after the ocean was gone.

“We could see the transition from purely marine ecosystems to when the ocean is no longer there, and we have a forest, and here we have a picture […] where now it’s dry land and dinosaurs are roaming around,” Velez said.

Terrain and care limit environmental impacts

Velez said that the potential environmental impact of digging up fossils is miniscule, especially in Saskatchewan.

“It’s ideal because we don’t need to remove any type of soil or forest because the badlands erode naturally with every season and it’s yielding the fossils,” she explained.

She explained that this means that fossils, such as dinosaur bones, and others are often exposed, giving them no need to dig extremely deep.

They also cooperate with local Indigenous and agricultural communities to ensure that no excavations take place that harm the land.

Respect for the land and the fossils a must

Egan mentioned that when researching in areas such as Grasslands National Park, that they make sure not to dig into the sage grasses. He said once the experiment is finished, the bones are returned.

By the public knowing where the fossils are buried, it poses a threat for illicit activity. “[…] fossil poaching can be a big problem,” said Egan.

One famous case involved the desecration of a dinosaur fossil in Grasslands National Park, “Where people took a deer antler to that beautiful tail and started to pry it out of the ironstone. They stole it and well, they stole what they could. It was in pieces,” Egan said.

Given cases of poaching and desecration are likely, both Velez and Egan emphasized on the importance of respecting the land and fossil. While they can not prevent all such cases, respecting the environment is key to both Velez and Egan’s research and they strive to make it a central part of their research.