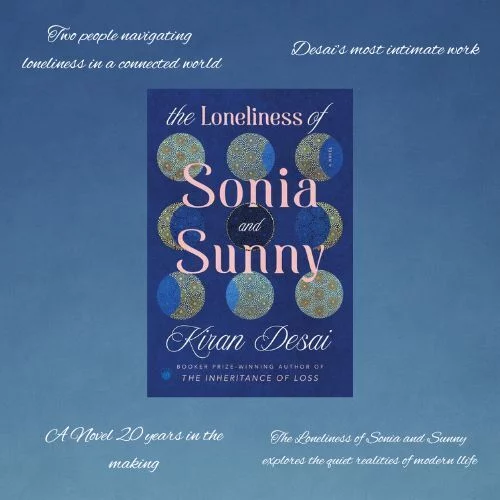

Desia’s recent publication goes beyond borders and decades and makes us wonder what it truly means to belong

After two decades of literary silence, Kiran Desia has returned with The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny that won her the Booker prize this year. This is a story where loneliness is neither a crisis nor condition but the background in which her characters exist. The novel is a meticulous study of two people adrift in the modern world, and of the quiet, persistent ache that comes from never belonging anywhere.

Desia’s book is both global and intimate. Set between India and the United States, it follows two individuals who are neither truly connected nor entirely apart.

Book’s Protagonists

Sonia Shah is a student and an aspiring artist in Vermont. She finds herself trapped in an affair with Illan de Torjeen, a celebrated painter who uses her as a muse, student, and then as a possession. The affair leaves her diminished, both as a person and an artist. When she returns to India, her idea of home collapses because the country she had left has changed, and her family feels foreign.

Through Sonia, Desia asks a piercing question: can art ever bridge the gap between where you came from and where you are now? You put the book down and realize that not just the past and present; you could never fully bridge the gap between the versions of yourself.

Sunny Bhatia’s arc, by contrast, is a study of self-conscious success. Working as a journalist in New York, he writes about migration and belonging while living a life that feels unmoored. His work grants him access to the stories of others but distances him from his own. His long-term partner accuses him of reporting life instead of living it. Desia uses that accusation as a quiet indictment of the modern intellectual class.

When he reluctantly returns to India, for familial reasons, he has to board an overnight train where he encounters Sonia by chance. Desia uses the physical space of the train, its narrow aisles, rhythmic movements, dim compartments, as metaphors for transit itself between countries, selves, and different versions of belongingness. It’s a scene that shows Desia’s gift for tension without confrontation, an emotional choreography that feels painfully true to life. The moment is quiet, accidental, yet it forms the book’s turning point as nothing overtly happens, but everything shifts, like the shift in the air before a storm.

Desia uses the scene to construct a narrative of encounters and echoes between generations, cities, and between memory and modernity. Both families had once thought of arranging a marriage between them, a fact that hangs in the background like an unspoken inheritance. It is one of Desia’s subtle commentaries on how cultures can, at times, treat intimacy as a social arrangement rather than emotional.

Author’s unique sense of writing

Desia’s writing has always been praised for its detail. Her sentences are clean, deliberate, and full of insight. When she describes Delhi’s suffocating heat or Vermont’s sterile clam, the imagery never distracts from what matters, the truth of the moment. The novel’s atmosphere is vivid but restrained, always grounded in psychology.

Desia does not build her story on dramatic events. Instead, she lets the tension live in everyday moments; in the quiet unease of returning to a childhood home that no longer feels like yours and the self-doubt of a career built on other people’s stories. She explores how ambition and pursuit pave the way to loneliness.

This is a novel about distance between people, countries, silences, and the selves we leave behind. – Zinia Jaswal

About halfway through the book, Desia introduces another subtle shift. The story stops being about whether Sonia and Sunny will reconnect and starts being about what connection means in a fractured world. Their conversations are slow and hesitant, filled with unfinished sentences and long silence, the hollow successes they can no longer defend. But through that restraint comes honesty. They don’t offer comfort but the truth to each other.

It is one of the most mature portrayals of human intimacy in contemporary fiction, built not on passion but on human understanding. Desia writes about these moments with precision and cold cruelty. She sees the human frailty behind them.

Audiobook upholds book’s essence

The audiobook version, narrated by Sneha Mathan, amplifies the pain in the story beautifully. Mathan’s performance is remarkable not only for theatricality but for restraint. Her voice carries the rhythm of Desia’s prose; steady and measured but also full of feeling.

Listening to Mathan read is like being guided by the novel’s silences. The pauses, the hesitations, the faint tremor in tone; they all serve the story’s emotional architecture.

In the novel’s final pages when Sunny and Sonia part again, her narration holds stillness, not of tragedy but of understanding. Mathan’s voice deepens the text’s intimacy, making loneliness sound like something lived rather than just imagined.

Human emotions in the most raw form

What makes The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny especially powerful, is its refusal to exaggerate. Desia writes about displacement without romanticizing it, about ambition without judgment, and about loneliness with pity. The book moves between social classes, continents, languages, yet it never loses focus on the small human details. A mother’s controlling affection, an artist’s private crisis, a journalist’s quiet collapse under the weight of relevance can all be clearly seen.

By the time the novel closes, there is no catharsis, no sudden revelation. Sonia and Sunny do not find each other, nor do they lose each other entirely. They simply go on with life, two people carrying the same solitude in different directions living with the consequences of modernity. The cost of our endless striving, the erosion of intimacy, the quiet grief that follows us across oceans is deafening in the book’s silent end. Desia refuses to give them closure because in her view, modern life rarely provides the luxury of closure.

The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny at 700 pages moves slowly, almost defiantly, but its pace is what gives it weight. It lingers in the details, a train-station, a thought left unsaid, and many quiet spaces. The novel’s slowness mirrors its subject of how emotion gathers quietly. The long, uneven rhythm of loneliness itself builds an archive of human connection. The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny is not just a novel about two people, it is about the world they live in. The fractured yet connected world yearning to find meaning in the noise of modern life.